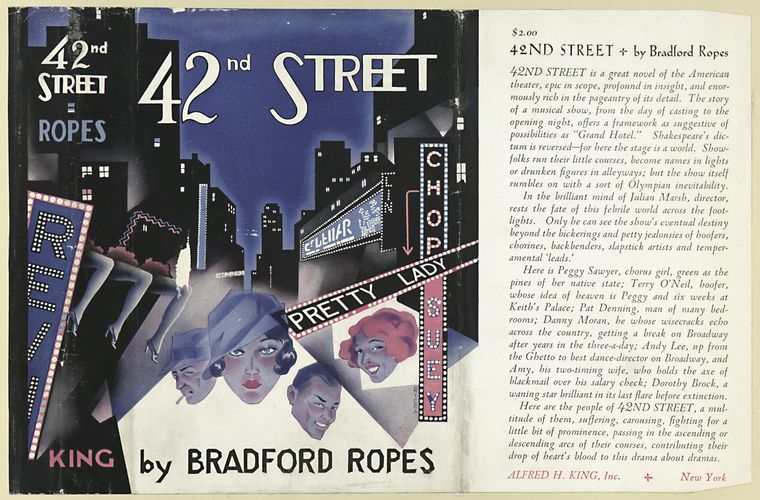

In the dust-jacket marketing for Ropes's 1932 novel 42nd Street, publisher Alfred H. King touted the book: "42nd Street is a great novel of the American theater, epic in scope, profound in insight, and enormously rich in the pageantry of its detail.... Shakespeare's dictum is reversed, for here the stage is a world. Showfolks run their little courses, become names in lights or drunken figures in alleways; but the show rumbles on with a sort of Olympian inevitability. "

Nobody would have appreciated the allusion to Jaques's As You Like It "seven ages of man" speech more than Ropes himself. In the first chapter of Greasepaint Puritan (in which I will fully cite the sources previewed here), I discuss Ropes's passionate and precocious love for Shakespeare's plays. As a youth, Ropes clearly gravitated toward not only the magical, but the metatheatrical, aspects of so many of the Bard's works. One of his earliest theatrical efforts drew from A Midsummer Night's Dream and Ropes wove Shakespearean allusions and resonances into all four of his backstage novels (also including Stage Mother, Go Into Your Dance, and the Boston-set Mr. Tilley Takes a Walk).

"At the age of seven, his favorite author was Shakespeare," revealed one profile, and another one elaborated: "When he was only eight, he started to rewrite Shakespeare in his own words!"

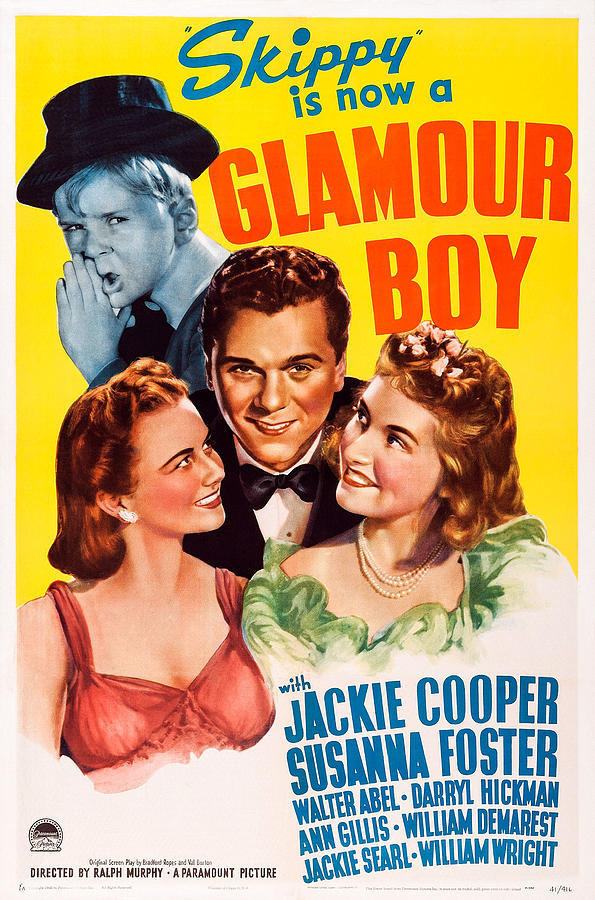

Another source revealed: “One of his former schoolmates…tells us how precocious and intense he was in his early interest in the drama and in the stage generally. Before he was 7 years old he had read all the plays of Shakespeare…. He had all the temperament that traditionally accompanies genius and if his audience was not duly appreciative of his rendition of Hamlet, for example, he did not hesitate to hurl a brick at it, or any other handy missile.” (Later on, hurling a self-deprecating brick backward in time at himself, Ropes satirized arrogant wunderkinds in the screenplay of his hilarious 1941 self-reflexive Hollywood comedy, Glamour Boy).

Did Ropes really read all 37+ plays by William Shakespeare by the age of 7? It's easy to sniff hyperbole in this account. Nevertheless, it's clear that at the age of the "whining school-boy," Ropes had started to read voraciously through the words of Shakespeare--and that the Bard's vision of the world as one of messy, multitudinous, sometimes Machiavellian theatricality formatively inspired Ropes in his later conception of 42nd Street. "That's entertainment," indeed.

"At the age of seven, his favorite author was Shakespeare," revealed one profile, and another one elaborated: "When he was only eight, he started to rewrite Shakespeare in his own words!"

Another source revealed: “One of his former schoolmates…tells us how precocious and intense he was in his early interest in the drama and in the stage generally. Before he was 7 years old he had read all the plays of Shakespeare…. He had all the temperament that traditionally accompanies genius and if his audience was not duly appreciative of his rendition of Hamlet, for example, he did not hesitate to hurl a brick at it, or any other handy missile.” (Later on, hurling a self-deprecating brick backward in time at himself, Ropes satirized arrogant wunderkinds in the screenplay of his hilarious 1941 self-reflexive Hollywood comedy, Glamour Boy).

Did Ropes really read all 37+ plays by William Shakespeare by the age of 7? It's easy to sniff hyperbole in this account. Nevertheless, it's clear that at the age of the "whining school-boy," Ropes had started to read voraciously through the words of Shakespeare--and that the Bard's vision of the world as one of messy, multitudinous, sometimes Machiavellian theatricality formatively inspired Ropes in his later conception of 42nd Street. "That's entertainment," indeed.

Pictured above: Pierre-Emile Jeannest, "Child from Shakespeare's Seven Ages of Man," c. 1850

RSS Feed

RSS Feed