My book-in-progress, under its working title Greasepaint Puritan: Boston to 42nd Street in the Gay Backstage Novels of Bradford Ropes, is currently in the works. In the spirit of Julian Marsh doing a show, I'm excited to start a blog!

In Greasepaint Puritan, I'll recount the untold story of Ropes, the enigmatic author of the original 1932 novel 42nd Street, as he moved between "Proper Boston" and naughty, bawdy 42nd Street; American vaudeville, the European variety stage and Hollywood films; and from the worlds of dance and theater to popular fiction, as the writer of four wildly entertaining novels, "embellished with the pungent aphorisms of Times Square," all of which provide candid and colorful views of working backstage, with a particular focus on the lives and relationships of gay men, and the on- and offstage roles of women. These are: 42nd Street (the source of the legendary 1933 Warner Brothers film, and 1980 Broadway musical); Stage Mother (1933); Go Into Your Dance (1934) and the later Mr. Tilley Takes a Walk (1951).

In later entries in "The World of Bradford Ropes," I'll go beyond the pages of my book to share selections of my archival research about Ropes; his friends, inspirations and collaborators; and the worlds of show business among which he so fluidly danced. This research process has spanned the last four years and I've found considerably more than I'll be able to include in the book. I highly recommend Richard Brody's 2020 essay "What to Read and Stream: The Remarkable Out-of-Print Book That Inspired 42nd Street" as an excellent introduction to Ropes's source novel.

The best way to get to know Ropes's slangy and acerbic voice is through his novels (two of which, 42nd Street and Go Into Your Dance, have recently re-appeared in print). But he also worked in Hollywood from 1933 through 1950, as contracted with Republic Studios but also freelancing with MGM, Paramount, and more. Ropes wrote or co-wrote the screenplays for over three dozen films: ranging from musicals; to slapstick comedies (starring both Abbott and Costello, and Laurel and Hardy); to singing-cowboy westerns starring Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, to even a few film noirs. Ropes was a deft, versatile scenarist and screenwriter, who wrote in all kinds of collaborative configurations and contexts--but the best Ropes screenplays are the ones in which he took the lead in writing the dialogue, which is consistently witty and pungent, in films filled with self-reflexive show business satire, some with a surprisingly modern flavor. Though most of these are currently not streaming and somewhat hard to get, they are well-worth seeking out (I've used retailers like Zeus DVDs for the more obscure ones). Here are my recommendations for a few of the most exemplary Ropes screenplays:

1) Stage Mother (1933; MGM); directed by Charles Brabin

Working with John Meehan, Ropes adapted his own novel for MGM, in a big-budget musical melodrama starring Alice Brady as the title character Kitty Lorraine and Maureen O'Sullivan as her talented but stage-shy daughter Shirley, hurled into show business by her indomitable mother (sound familiar?). The source of the Freed-Brown standard "Beautiful Girl" (more famous from Singin' in the Rain), Stage Mother shows Ropes adapting his novel with a considerable degree of fidelity to the book--though its Hollywood ending grants the title character a redemption that remains much more elusive in the novel. Brady lends nuance and grandeur, ferocity and tenderness, to her psychologically astute performance as Kitty in a film also featuring Franchot Tone, Phillips Holmes, Ted Healy (of the Three Stooges), and Jay Eaton as a fey dance instructor.

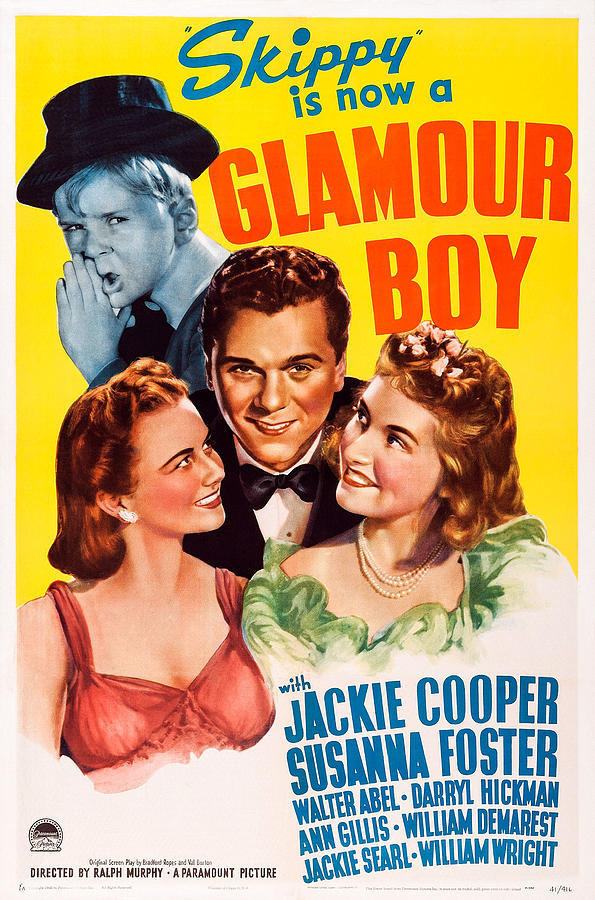

2) Glamour Boy (1941; Paramount); directed by Ralph Murphy

Other than Stage Mother, Glamour Boy is the Ropes screenplay that most directly channels his novelistic voice: it's a tart, hilarious and affecting meta-satire in which the 18-year-old Jackie Cooper, playing a washed-up child star named Tiny Barlow, coaches Dickens-quoting radio whiz kid Billy Doran (Darryl Hickman) to star at Marathon Studios in a remake of his biggest hit: Skippy. Paramount re-used footage of Cooper's own famous early-Depression blockbuster, while allowing Ropes and collaborators Val Burton and F. Hugh Herbert to skewer the commodification of its child stars and Hollywood sentimentality in its many forms. Cooper is appealingly game as Tiny, and Edith Meiser wonderful as movie-mogul Gal Friday Jenny Sullivan, in a comedy that will appeal to fans of contemporary show-biz satires like "Flack" and "The Other Two."

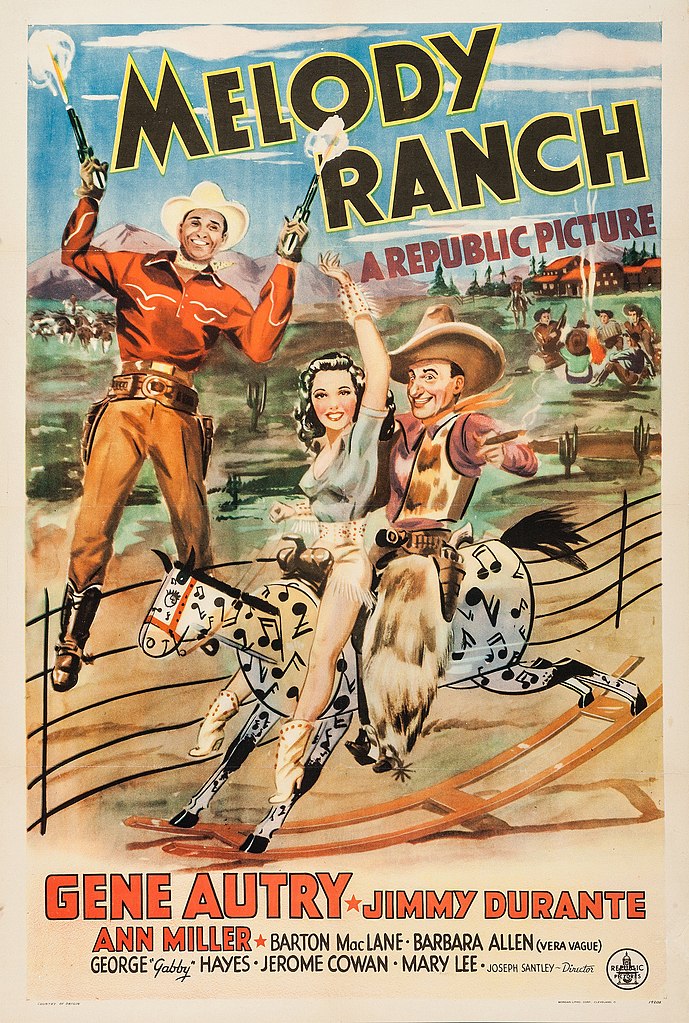

3) Melody Ranch (1940; Republic); directed by Joseph Santley

The singing-cowboy western was a mainstay of Ropes's home studio of Republic--but only Melody Ranch unleashes the vaudevillian chaos of Jimmy Durante upon the Arizona town of Torpedo, and the charms of Ann Miller into the somewhat wooden arms of Gene Autry. The latter plays a fictionalized version of himself: a cowboy radio star, who, returning to his hometown to accept the role of honorary sheriff for the Frontier Days Celebration, remains behind to rid the town of racketeers. Broadway musical comedies like Whoopee! and Girl Crazy had previously blended New York city slickers and bronco busters; the sensibility of New York immigrant comedy and western tropes. Here, Ropes (working with co-writers Jack Moffitt and F. Hugh Herbert) takes pleasure in satirizing and queering the genre's machismo. At a town reception, an eccentric young townswoman named Veronica Whipple (played by brassy comedienne Barbara Jo Allen) welcomes Autry back to Torpedo with a light verse:

Here’s to our wondrous Torpedo

Neath shining hills and grassy…meedow.

I love it here in the Old Far West

Of the rest of the world I am wearied

Yes, it’s wonderful here in the Old Far West

Where women are women, and men are…period.

Mary Lee, Republic's answer to the young Judy Garland (and a superb, underrated singer), belts "Torpedo Joe," a song (with music by Jule Styne) loaded with censor-defying camp double entendres, leading Whipple to object: “Stop it…where did you learn that deplorable song?”

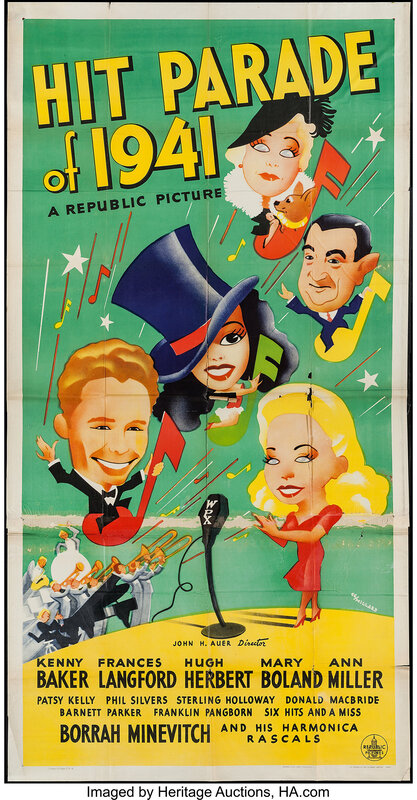

4) The Hit Parade of 1941 (1940, Republic); directed by John H. Auer

While Ropes's backstage novels are primarily concerned with theatrical show business--from Broadway to vaudeville to burlesque--his Hollywood films poke fun at other media technologies, including radio. In the 1940 MGM film Hullabaloo, for which Ropes conceived the idea with Val Burton, Frank Morgan flaunts his signature flim-flam: as a radio star who causes a national panic when he announces a Martian invasion a la "The War of the Worlds."

In 1937 and 1941, Ropes also engaged with radio in two of Republic's popular Hit Parade series, which showcased airwave crooners like Frances Langford and Kenny Baker (as Pat and David, the love interests here), as well as vaudeville stars and specialty acts. Filled with a delightful cast of zanies (Mary Boland, Patsy Kelly, Phil Silvers, Hugh Herbert, Sterling Holloway, and Franklin Pangborn among them), The Hit Parade of 1941 is the second Ropes film to anticipate Singin' in the Rain. Here, Ann Miller's aspiring diva Annabelle Potter, an ace dancer but a lackluster singer (unlike Miller herself), accepts Langford's lip-syncing aid after her imperious department store tycoon mother (Boland), the sponsor for WPX's "Trading Post of the Air," threatens to pull funding if Annabelle doesn't star in the show. Annabelle sings into a dead microphone as Pat unhappily croons in a hidden studio (complete with early television) offstage. But Pat's sister Judy (Kelly) reveals the woman behind the curtain, as Langford's voice pours out of Annabelle's turned-on mic. The Kathy Selden/Lina Lamont vibes are strong in a film that once again illustrates Ropes's inventiveness and savvy with show business satire.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed